Recursion

an overview of the substitution method and recursion trees

Introduction

This note assumes you know what an algorithm is, but as a quick refresher according to Jeff Erickson, “an algorithm is an explicit, precise, unambiguous, mechanically-executable sequence of elementary instructions, usually intended to accomplish a specific purpose.”

Good algorithms are incredibly useful, but sometimes a problem might not have a clear algorithmic solution. Worse, it might even be impossible. A powerful method to solve an unknown problem is to make a reduction to one or more simpler problems that can be solved by known algorithms. The reduction of a problem can even be into smaller instances of itself, breaking up repeatedly until reaching one of several base cases. This is called recursion. Divide-and-conquer is a general pattern for solving a problem using recursion:

- Divide the problem into independent smaller instances of the same problem.

- Conquer or solve the smaller instances by recursion.

- Combine the solutions of the smaller instances into a solution of the original problem.

It is often easier to think of recursion without thinking about solving the smaller subproblems yourself. Instead, think of a worker solving all of the subproblems for you. You must know how to relate the problem to smaller versions of itself, and how to solve any of the smallest instances that can no longer be simplified. Once you simplify the original problem, hand the subproblems off to the worker. They will simplify and solve the subproblems for you, so let them work in peace.

A natural way to characterize the running time of a divide-and-conquer algorithm is to use a recurrence, or a function defined in terms of itself. So far we have been using the words smaller and simpler interchangably. Indeed, in terms of analyzing the running time of an algorithm we often consider the input size, denoted \(n\).

As a quick example, consider the following recurrence for merge sort:

\[MergeSort(n) = \begin{cases} \Theta(1) & n = 1 \\ 2MergeSort(n/2) + \Theta(n) & otherwise \end{cases}\]Merge sort consists of splitting the unsorted input array into two roughly equal halves, recursively sorting those halves, and then merging the sorted halves into a sorted version of the input array. The recurrence says it takes constant \(\Theta(1)\) time to sort an array with 1 element, or \(2MergeSort(n/2)\) time to sort the halves and linear \(\Theta(n)\) time to merge the halves into a solution. It is well-documented the overall running time is \(\Theta(n \log{n})\).

The Substitution Method

Consider a similar recurrence:

\[T(n) = 2T(\lfloor{n/2}\rfloor) + n\]This has the same asymptotic complexity as merge sort because in general floors, ceilings, and even lower order terms can be removed entirely from divide and conquer recurrences using domain transformations. So since we know it’s like merge sort, how do we show \(T(n) = O(n \log{n})\)? Using the definition of big O, we must show there exist positive constants \(c\) and \(n_0\) such that:

\[T(n) \leq cn\lg{n}, \quad n \geq n_0\]where \(\lg{n} = \log_2{n}\). To do this, we must assume the above inequality holds for some positive \(m < n\), particularly \(m = \lfloor{n/2}\rfloor\). Plugging this in gives:

\[\begin{flalign} T(n) & \leq 2(c\lfloor{n/2}\rfloor\lg{\lfloor{n/2}\rfloor}) + n&\\ & \leq cn\lg{n/2} + n&\\ & = cn\lg{n} - cn\lg{2} + n&\\ & = cn\lg{n} - cn + n&\\ & \leq cn\lg{n} ~ \text{holds for} ~ c \geq 1 \end{flalign}\]This looks good for the recurrence, i.e. the inductive step. But we also have to show the inequality holds for the base cases, i.e. for \(c\) and \(n_0\). Notice if we choose \(n_0 = 1\) as the base case, our recurrence says \(T(1) = 2\lfloor{1/2}\rfloor + 1 = 1\), but the inequality says \(T(1) \leq c1\lg{1} = 0\), a contradiction!

Luckily, we can remove the troublesome \(n = 1\) base case from the inductive proof. It’s still a base case of the recurrence, but we don’t have to use it in the inductive step. Intuitively, we don’t need to recurse on an array containing a single element because it is already “sorted”. We set \(T(1) = 1\), and look for other base cases to use in the inductive proof.

Observe that \(T(n)\) does not directly depend on \(T(1)\) for \(n > 3\). Using \(T(1) = 1\), we find that \(T(2) = 4\) and \(T(3) = 5\). We can use these as the base cases in the inductive proof by setting \(n_0 = 2\). Now we just need to find a value for \(c\) so that \(T(2) \leq c2\lg{2}\) and \(T(3) \leq c3\lg{3}\). It turns out any \(c \geq 2\) is sufficient.

This was an example of the substitution method for solving recurrences:

- Guess the form of the solution.

- Use mathematical induction to find \(c\) and \(n_0\) showing the solution works.

Recursion Trees

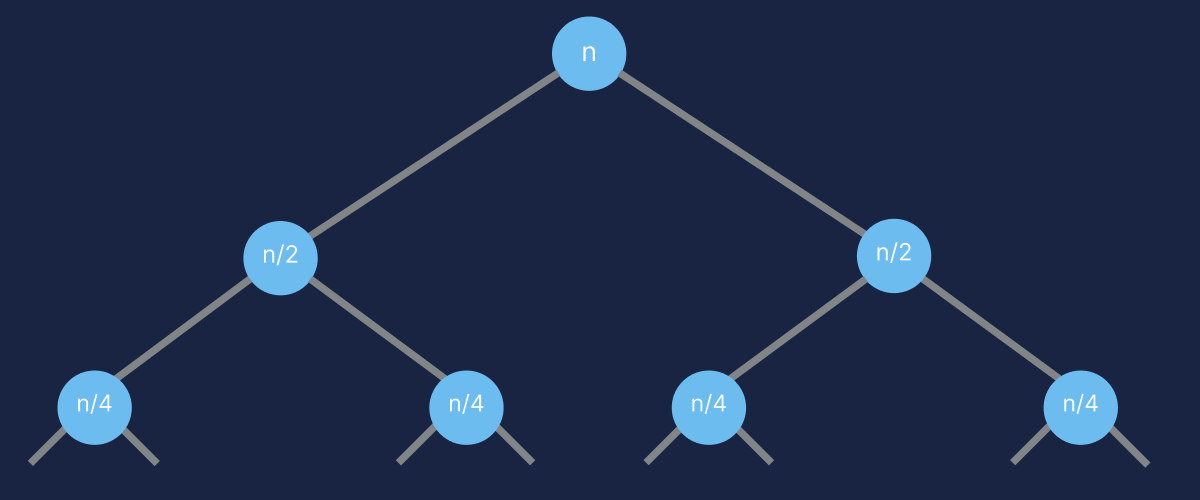

Another way to see that merge sort is \(O(n \log n)\) is by looking at its recursion tree. That is, a rooted tree where each node represents a subproblem, and has a value corresponding to its contribution to the overall running time. The root of the tree represents the original problem. Edges represent recursive calls to other subproblems, and do not contribute to the running time of either of their endpoints. Leaves represent base cases. The overall running time can therefore be thought of as the sum of node values.

The value of each node comes from the nonrecursive work done for that subproblem. One can see the root value \(n\) comes from the \(\Theta(n)\) in the recurrence:

\(MergeSort(n) = 2MergeSort(n/2) + \Theta(n)\).

The \(2\) edges from the root are because \(MergeSort(n)\) makes \(2\) recursive calls, and the value of the children of the root \(n/2\) comes from the \(\Theta(n/2)\) in \(MergeSort(n/2)\). Let \(d\) be some depth within the tree, starting with \(d = 0\) at the root. In general, there are \(2^d\) nodes at each depth or level of the tree, and each node at that level has a value of \(n/2^d\).

Since we’re talking specifically about merge sort, and because it doesn’t actually affect the asymptotic bounds, let the base case of the recurrence be \(T(1) = 1\). As stated earlier, \(T(n)\) is equal to the sum of all node values in the tree. Suppose there are \(L\) levels in the entire tree, so there are \(2^L\) leaves with value \(n/2^L\). Since the leaves are base cases, we know \(n/2^L = 1\), which tells us the number of levels in the tree \(L = \lg{n}\).

There is one more key fact that allows us to determine the running time: the sum of node values at each level of the tree is \(n\). Putting it all together, the recursion tree consists of \(\lg{n}\) levels that each contribute \(n\) time, so the overall running time of \(T(n)\) is \(O(n \lg n)\).

In general, there are many recurrences of the form \(T(n) = r~T(n/c) + f(n)\) with \(\Theta(1)\) base cases. The example we just saw had \(r = c = 2,\) and \(f(n) = n\). So, a recursion tree for this general recurrence is a complete \(r\)-ary tree where each node at depth \(d\) has value \(f(n/c^d)\). The running time is the level-by-level sum of node values:

\(T(n) = \sum\limits_{i = 0}^{L}{r^i \cdot f(n/c^i)}\).

We saw that \(L = \log_c{n}\) when \(n_0 = 1\) because \(n/c^L = n_0\) is the base case. We also saw there are exactly \(r^L = r^{\log_c{n}} = n^{\log_c{r}}\) leaves. The last key fact was really that the values of the leaves sum to \(n^{\log_c{r}} \cdot \Theta(1) = \Theta(n^{\log_c{r}})\).

The sum we just saw is a geometric series, whose asymptotic growth is given by the largest term in the series. With this in mind, there are three common cases where the running time is easy to evaluate:

- Decreasing: if every term in the series is a constant factor smaller than the previous term, then the running time is dominated by the value at the root of the tree, and \(T(n) = \Theta(f(n))\).

- Equal: if all terms in the series are equal, then \(T(n) = \Theta(f(n) \log{n})\). Merge sort falls under this case.

- Increasing: if every term in the series is a constant factor larger than the previous term, then the running time is dominated by the sum of leaf values, so \(T(n) = \Theta(n^{\log_c{r}})\).